Almost universally condemned as one of the worst Doctor Who serials ever, The Dominators was the serial Patrick Troughton personally requested be screened at the convention he was attending at the time of his death. Perhaps Troughton could see something of merit in The Dominators that fans and critics were unable to discern. But then again, in 1987 there weren’t many extant Second Doctor serials available. There aren’t many more accessible today. That’s probably reason enough to at least try to detect something favourable about the serial. Thankfully the good contributors to Celebrate Regenerate have come to our rescue and said this about The Dominators:

I think I knew The Dominators was the weakest of the bunch. But I still loved it: it was funny. It’s the only Doctor Who story I know of that’s based on a clash of household furnishings. Guys wearing sofas invade a world of people dressed in curtains. The natives immediately surrender to them despite the fact that they’re incompetent (those other ten galaxies must have really been pushovers). And then there are the Quarks. Small, slow, waddling, penguin-esque with squeaky voices and very low-capacity batteries. But at the end of the day , I love the Dominators …

Edited by Lewis Christian, Celebrate Regenerate is a fan produced chronicle of every Doctor Who episode

Save for its slowness and distinct lack of plot, the principal criticism directed at The Dominators is the writers’ reactionary premise that pacifism is abhorrent and pacifists gullible and unintelligent. In their third and final outing as writers for Doctor Who Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln took a direct swipe at the growing anti-war movement. The Dulcians are pacifists and presented as unquestioning morons. Although they have two hearts they are physically weak and not use to manual labour. When forced to labour as slaves to the aggressors, the Dominators, they are next to useless and are seen to struggle under the burden of moving heavy rocks. The Dulcians’ education system appears to prioritize rote learning over intellectual enquiry and they accept any statements as fact until they are otherwise proved false. It isn’t too hard to envisage what Haisman and Lincoln’s perception of anti-war protestors were.

The Dominators was not Doctor Who’s first anti-pacifist adventure. That dishonour goes to Terry Nation’s The Daleks in which the gorgeous Thals are pilloried for their being unprepared to fight . In my review of The Daleks I examined Nation’s contempt for the 1930’s British policy of Appeasement. Unlike the Thals, Haisman and Lincoln do not afford the Dulcians any redemption. They are portrayed in an unfavourable light throughout the whole of the serial. Given that Doctor Who has generally taken a more liberal view on political issues this contempt for pacifism is all the more extraordinary.

More than 40 years later such distain for pacifism was again evidenced in Toby Whitehouse’s Series Six story, The God Complex (2011). This time, however, a reactionary political message was veiled in humour. When the Eleventh Doctor asks Gibbis, a native of Tivoli, how he arrived at the “hotel” his response was enlightening – “I was at work. I’m in town planning. We’re lining all the highways with trees so invading forces can march in the shade. It’s nice for them”. Tivoli is the most conquered planet in the galaxy and its residents have resigned themselves to being constantly overrun. Accordingly they welcome invading armies and their national anthem reflects the ease with which they accept domination – “Glory to <Insert Name Here>”.

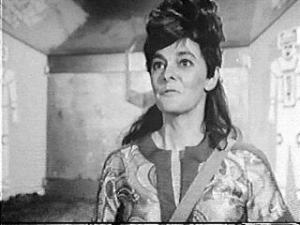

What I also found disturbing about The Dominators was the patriarchal nature of the Dulcians’ society. Only men, and old ones at that, are members of their governing council. Certainly there are numerous other Doctor Who serials which are guilty of not positively representing women, however The Dominators totally disenfranchises them. I would hope that this says more about the writers’ views than those espoused by the producers of Doctor Who. That being said, the decision to give the Quarks childish female voices is bizarre, to say the least. Hitherto all monsters, without exception, have had masculine voices even if their bodies are not specifically gendered. The one and only time that a woman is used to voice a monster, the voices are clumsy and laughable. It left me wondering if this was some form of bad joke in which women, in general, were being ridiculed.

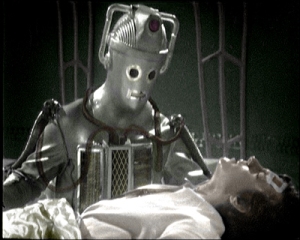

Unfortunately the Quarks proved to be appalling monsters. Small in stature, school children were encased within them for the filming. They shuffled around, always looking as though they were about to tumble over, and had arms that were even more impractical than the Daleks’. They were easily defeated, at one stage by a conveniently light boulder pushed from a hill top by Cully, the only resident of Dulkis to rebel from their pacifism. Created by Haisman and Lincoln specifically for their marketing potential, the Quarks were almost the subject of legal proceedings between the writers and the BBC. Relations between the writers and Doctor Who deteriorated further when the serial was cut from six episodes to five and substantially rewritten. Haisman and Lincoln sought to have their names removed from the credits and accordingly a pseudonym, “Norman Asby”, which was taken from the first names of the writers’ father-in-laws, was adopted.

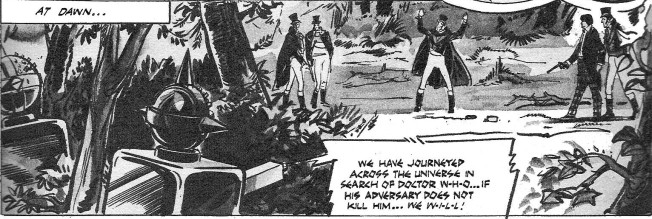

The marketing rights to the Quarks almost resulted in legal proceedings between the writers and the BBC

The Doctor’s ethics in The Dominators are also questionable. He is responsible for the deaths of the two Dominators after he places their atomic seed-device, intended to destroy the planet, onto the aggressor’s own space craft. This is plainly an example of lazy writing as it was the easy option for disposing of the bomb quickly. Surely the Doctor could have diffused it rather than acting as judge, jury and executioner.

Despite its many failing I surprised myself by actually enjoying The Dominators. Perhaps I was just relieved at watching the first complete serial since The Tomb of the Cybermen or maybe, just maybe, I could see in the story the good that Patrick Troughton evidently saw. I really don’t know, however I am sure that our next story, The Mind Robber, lives up to its reputation as Troughton’s favourite serial. Please join me for my next review as we enter the land of fiction.

Vivien Fleming

©Vivien Fleming, 2013.